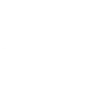

Senator George McGovern, who passed away in 2012 at the age of 90, is often remembered for his 1972 presidential defeat to Richard Nixon. Yet, his more enduring legacy may lie not in politics, but in public health. As chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs, McGovern presided over the release of America’s first official dietary guidelines in January 1977—a document that would ignite one of the most intense food industry battles in U.S. history.

At the press conference unveiling the report, McGovern spoke with quiet urgency:

“The simple fact is,” he said, “our diets have changed radically in the last fifty years, with very harmful effects on our health. These changes represent as great a threat to public health as smoking. The diet of the American people has become increasingly rich—rich in meat, in saturated fats and cholesterol, and in sugar.”

The committee’s report, titled Dietary Goals for the United States, made an extraordinary claim for its time:

“Almost all of the health problems underlying the leading causes of death in America—heart disease, cancer, diabetes, hypertension—could be modified by improvements in diet. We cannot afford to temporize. The public wants the truth, and today, we hope to lay the cornerstone for better health through better nutrition.”

But the truth, as McGovern and his colleagues soon discovered, was not welcomed by everyone.

Dr. Mark Hegsted of Harvard, one of the report’s scientific contributors, later recalled, “The meat, milk, and egg producers were very upset.” That was putting it mildly.

The International Sugar Research Foundation condemned the report as “unfortunate and ill-advised,” dismissing it as part of an “emotional anti-sucrose conspiracy.” The organization’s president scoffed:

“Simply stated, people like sweet things, and apparently the McGovern Committee believes people should be deprived of what they like. There’s a puritanical streak in certain Americans that leads them to become do-gooders.”

The Salt Institute joined the revolt, rejecting the very notion that Americans should reduce salt consumption. Even the claim that “improved nutrition could cut the nation’s health bill by one-third” was ridiculed. The argument, bizarre as it sounds, was that if people lived longer due to better diets, they would cost more in old-age care—so perhaps it was cheaper to let them die sooner. One researcher even quipped that banning tobacco might raise healthcare costs, since “the longer people live, the more expensive their care becomes.”

The National Dairy Council demanded that the report be withdrawn and rewritten with “industry participation.” As one commentator wryly noted, “As soon as Häagen-Dazs gives its blessing, then go for it.”

But no one reacted as furiously as the meat and egg industries. The president of the American National Cattlemen’s Association complained that meat was “never mentioned in a positive way,” only in connection with degenerative diseases. He warned ominously that if the guidelines were promoted “in their present form, entire sectors of the food industry—meat, dairy, sugar—may be so severely damaged that recovery may be out of reach.”

The president of the National Livestock and Meat Board went even further, declaring with moral conviction:

“Guided by my conscience, I am certain that the actions of the animal industries to ensure Americans are properly fed with abundant meat and other animal foods represent an honorable and morally correct course.”

The industry demanded that the committee withdraw the guidelines entirely and issue a “corrected” version. Their particular ire was directed at Guideline #2, which suggested Americans should decrease meat consumption to lower saturated fat intake.

Senator Bob Dole, ever the mediator, proposed a friendlier edit: change “decrease consumption of meat” to “increase consumption of lean meat.” He asked the cattlemen’s president, “Would that taste better to you?” The reply came instantly: “Decrease is a bad word, Senator.”

By year’s end, the committee relented. The revised guideline now read:

“Choose meats, poultry, and fish which will reduce saturated fat intake.”

But even that concession failed to appease the industry. They demanded the abolition of the entire nutrition committee and insisted that its functions be transferred to the Senate Committee on Agriculture—whose primary mandate was to protect food producers, not public health.

The New York Times captured the absurdity of this move in a memorable editorial:

“Placing the Committee on Nutrition under the Agriculture Committee is like sending the chickens off to live with the foxes.”

And that, astonishingly, is precisely what happened. The Senate Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs was disbanded, and its responsibilities were absorbed by the Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry—effectively placing the guardians of public nutrition under the control of the food industry itself.

Yet McGovern never surrendered. When later asked whether he could find solace in the Serenity Prayer’s plea for “the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,” he smiled and replied,

“I keep trying to change them.”